An In-depth Analysis of Joints: The Meeting Points of our Skeleton

This article provides an in-depth exploration of the two primary categories of joints in the human body: synovial and solid joints. It begins by defining what constitutes a joint and their overall purpose. The article then delves into the features, functions, and examples of synovial joints, which are characterized by a cavity filled with lubricating synovial fluid. The piece also discusses solid joints, where adjacent bones are directly connected by fibrous or cartilaginous tissue, and their role in stability and shock absorption. The conclusion emphasizes the importance of understanding the complexity of the skeletal system in improving treatments for joint-related ailments and enhancing human quality of life.

Analysis of Joints

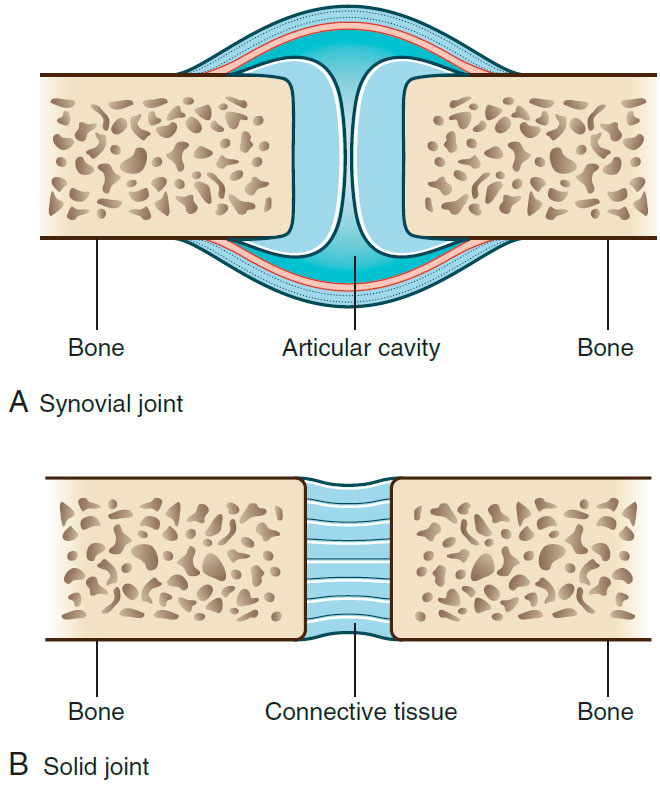

Joints, the pivotal meeting points of our skeleton, play a crucial role in facilitating movement and providing support. While all joints serve as the intersection of two or more skeletal elements, not all joints are created equal. This article delves into the two primary categories of joints: synovial joints, characterized by a cavity separating the skeletal elements, and solid joints, where components are bound by connective tissue.

The Fundamental Architecture of Joints

Before diving into the two categories, it’s important to understand what constitutes a joint. Essentially, a joint, or an articulation, is the anatomical location where two or more bones intersect. The primary function of joints is to provide motion and flexibility to the skeletal frame, along with offering mechanical support.

Synovial Joints: The Movers and Shakers

Synovial joints are the most common type of joint in the human body and are integral to our daily movements. These joints are characterized by the presence of a cavity, the synovial cavity, which is filled with a lubricating synovial fluid. This fluid helps reduce friction between the articulating bones, ensuring smooth and painless movement.

The key components of a synovial joint include articular cartilage, which covers the ends of bones, the articular capsule, which encloses the joint cavity, and ligaments, which add stability by connecting bones.

Examples of synovial joints include the knee, hip, elbow, shoulder, and wrist joints. These joints are further classified into different types based on their shape and movement, such as hinge joints (elbow), ball-and-socket joints (hip and shoulder), and pivot joints (neck).

01

Joints: A) Synovial joint; B) Solid joint.

Solid Joints: Bound by Connective Tissue

Contrasting with synovial joints, solid joints, also known as fibrous or cartilaginous joints, are where the adjacent bones are directly connected to each other by connective tissue, with no intervening joint cavity.

In fibrous joints, the bones are linked by fibrous tissue. Examples include sutures in the skull, where the bones are interlocked along a line of dense connective tissue, and syndesmoses, where the bones are farther apart but still connected by ligaments, such as the tibia and fibula in the lower leg.

Cartilaginous joints, on the other hand, are united by cartilage. These include synchondroses, where the bones are united by hyaline cartilage, like the growth plates in children, and symphyses, where a disc of fibrocartilage joins the bones, like in the spinal vertebrae or the pubic symphysis.

Although solid joints generally provide less movement than synovial joints, they play a crucial role in providing stability and shock absorption.

Conclusion

Understanding the architecture and function of different types of joints provides valuable insights into how our bodies move and function. From the synovial joints that offer us a wide range of motion to the solid joints that provide stability, the intricate design of our skeletal system is a testament to the complexity and efficiency of human biology. As we continue to uncover the mysteries of the human skeleton, each discovery brings us one step closer to improving treatments for joint-related ailments and enhancing our overall quality of life.